Flashback: Fall, 1994. The mayor’s job in Omaha comes open following the sudden resignation of P.J. Morgan. Crime is on the rise. Downtown Omaha is in peril. Many of the city’s major corporations are looking to relocate to the suburbs or, worse yet, leave the city altogether. A master plan designed to bring Omaha back from the brink of disaster existed, but the city needed the right person to get the job done. Enter Hal Daub.

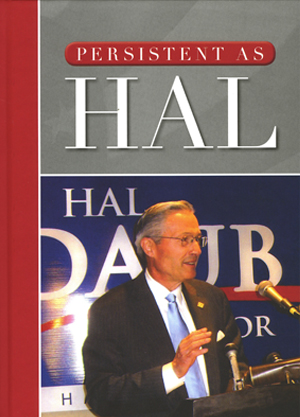

Persistent as Hal examines the legacy of longtime Nebraska politician Hal Daub, tracing his career from the military all the way through his various stops as a public official: Republican party leader, congressman, candidate for senate, mayor, and now university regent. Readers will come to know (and appreciate) the one trait that made it all possible for Daub—his persistence.

A peek inside

(after mergers the firm would become known as Deloitte and Touche, then eventually just Deloitte).

“I was good at it,” he said of his consulting career. “I was good at getting business for the company. I was a problem solver. I was enjoying the work, had a great job, working with wonderful professionals and outstanding international clients. My areas of expertise were not only tax, but special subjects like the classifications of independent contractors and the North American Free Trade Agreement,” (NAFTA).

If you were looking for Hal Daub in the early fall of 1994, you’d likely have found him somewhere with his head stuck in a book. His Omaha Public Library card was about to impact one of his life’s most important political decisions, whether or not to run for mayor of Omaha.

In 1994, it looked like Daub’s political career was over. Even he conceded that such an ending might have been a possibility. It appeared he would spend the rest of his career as a partner at Touche Ross, the “Big Eight” accounting and advisory services firm he had joined in 1990

close to the mayor’s office—interests they wanted to protect. To this day, Daub won’t say who these people were.

But they knew what they were talking about. In April, P.J. Morgan resigned. For some, the reasons were hard to understand. He had just been reelected with token opposition, a singular accomplishment. Had he been burdened by the responsibilities of the office, or was he grieving the recent death of his son? Whatever the reason, he wanted out. He took a post as president of Duncan Aviation in Lincoln. He’d just exchanged one set of responsibilities for another. So why had he left the mayor’s job at all? The move left many Omahans scratching their heads.

Daub’s NAFTA work had taken him to Canada, Mexico, Japan, and other parts of the world, often for weeks at a time. He enjoyed Touche Ross and took great satisfaction from being a lawyer. Then came the day that a group of Omaha businesspeople pulled him aside and offered him a nugget of information that might change his course. Rumor had it that Omaha Mayor P.J. Morgan was going to resign. The way Daub recalls it, rumors of Morgan’s resignation had not yet even hit the street.

This was protected information, offered by a reputable, albeit private, group of businesspeople with interests

Moreover, tourism and convention business was lagging. There weren’t enough downtown hotels, the convention facilities were small and obsolete and the city had a lame record of attracting first-rate traveling entertainment. Omahans, who loved country singer Garth Brooks, were upset their city couldn’t draw an act of his caliber.

City leaders were trying to deal with the problems, but the problems were large. The city had completed the first phase of its master plan in November 1993. Drafted by then-Mayor Morgan, it called for fewer strip malls, the redevelopment of the city’s older neighborhoods and stronger business growth downtown.

A fog surrounded Morgan’s sudden departure, and that same fog enveloped Omahans’ view of the future of their city. What residents could see didn’t please them. Ever since 1986, when energy colossus Enron had moved its corporate headquarters to Houston, Omaha, particularly the downtown business district, seemed headed for a downward spiral. True, Enron eventually melted down and wafted away in the Texas wind, so the economic holocaust associated with the company could have blasted Omaha if it had stayed. At the time Enron left, however, the blow to Omaha’s self-image was devastating. The city lost about 1,000 jobs and was marked as a place where major employers didn’t want to be.

“Think about the well-thought-out, new master plan that started under P.J. Morgan,” he said later. “If you build on that, and begin to think about it, you ask yourself: Why isn’t something happening? We have all these visions and initiatives. That’s really what I asked myself when I studied the question of ‘Should I run for mayor?’ Why hasn’t something been done? Why all the talk?”

But the problems went far beyond the downtown district. In fact, the city was growing too far beyond the downtown. Omaha was spreading rapidly to the west, so quickly that city officials were having trouble delivering basic services to west Omaha residents. The Omaha World-Herald reported that Omaha’s land mass had doubled since 1960, while its population had grown only 10 percent. Urban sprawl wasn’t the only issue. Residents were depressed over the city’s shabby appearance, upset with rising crime and displeased with the police department.

Daub understood these challenges and believed he knew why they persisted: city leaders had made plans to deal with them, but hadn’t followed through.

Every time it seemed his political career might be over, Hal reminded us he is perpetually just getting started. After Congress, he found new life as Omaha’s mayor and jumpstarted his hometown.

Every time it seemed his political career might be over, Hal reminded us he is perpetually just getting started. After Congress, he found new life as Omaha’s mayor and jumpstarted his hometown.